Hook, Line and Sinker: The Temporal Tightrope of Modern Dawah

19th March 2023

Recent Posts

Dawah: The act of inviting or calling people to embrace Islam

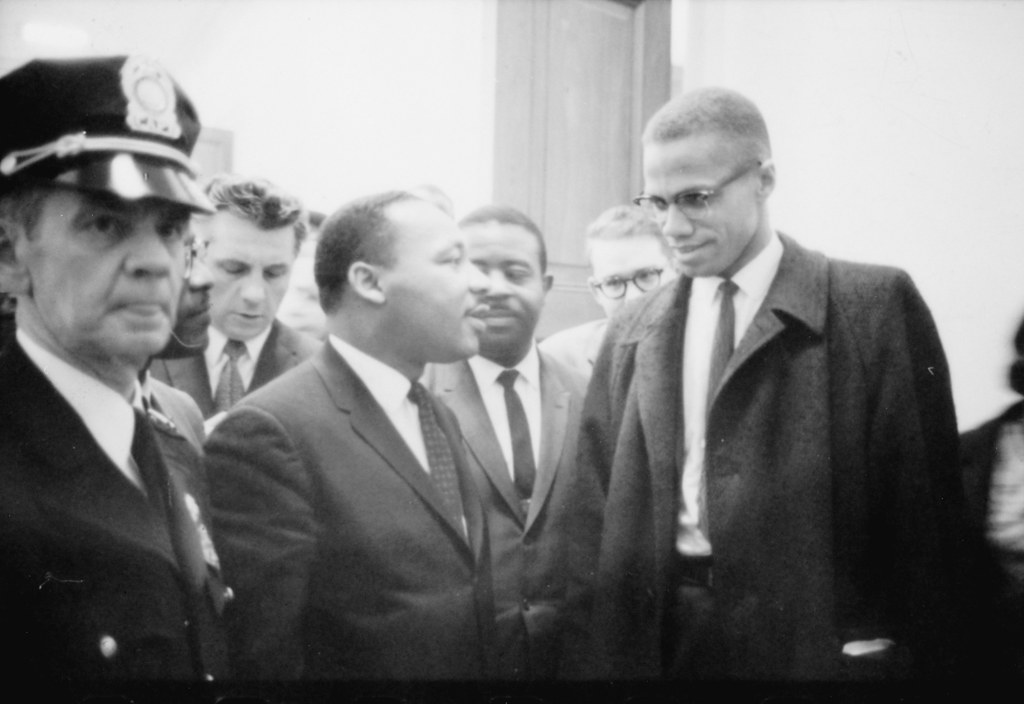

Perhaps the most renowned Muslim figures to emerge in the 20th Century are Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali. Notable in sociopolitical activism and sport respectively, both X and Ali have held acclaim amongst the public, and can be quickly recognised as figures of American popular culture. The world over, their prominence has presented Muslims with an opportunity to identify themselves with people who represented them in being openly practising Muslims. For a community that has often been subject to interrogative scrutiny at best, and vilified at worst, Muslim public figures such as these can be a refreshing source of empowerment. Beyond that, the admiration both Ali and X receive across religious, cultural, national and generational parameters can be a source of community pride. Sometimes even a reflexively wielded, decorated shield to deflect popular culture’s recurring pointed arrows firing against either Muslims or Islam.

X and Ali are also similar in having trod the same meandering path in their journey through religion. Both had joined, and eventually left, the Nation of Islam, ultimately remaining Sunni Muslims throughout their lives. To some, Elijah Muhammad has provided and continues to inspire greater reverence than either X or Ali, owing to his position in the Nation of Islam. Acknowledged as the ‘Supreme Minister’ of the movement, Muhammad was the religious and organisational leader of the Nation when X and Ali were members.

And the sole individual transcending Muhammad’s station is Muhammad W. Fard. With irregular, fluctuating beliefs and practices being peppered throughout the movement’s history, at times closer to conventional Islamic practice and at times further, the current declaration of the Nation’s beliefs holds the following position:

The twelfth criterion of belief listed on the movement’s website, this facet stands out as the most significant deviation from Islam recognised by the majority of Muslims. Significant enough to be considered a belief in disbelief—something beyond the pale of Islam.

Preceding this belief, however, are numerous others. These include the prohibition on “race mixing” and advocating the separation of the USA to accommodate a separate space for African American people. The Nation is not limited to being a religious organisation. Making it a distinct group from the larger Muslim community, the ummah, is its role as an organised social and political movement focussed on directing the experiences of African Americans in the USA.

The organisation has drawn many people in the near century it has existed, including a range of celebrities. However, these figures have not gone on to represent Islam the way that Ali and X have. Etta James defined herself as a Muslim for a decade within the organisation, eventually practising Ahmadiyya due to the influence of her partner John Lewis, with varying degrees of devotion. Snoop Dogg became a member of the Nation of Islam, even contributing financially to the organisation in 2009. Recently, Snoop Dogg released a gospel album, and declared himself a “born-again Christian”. Ice Cube, whilst still identifying as a Muslim, stated in 2017: “…I’m gonna live a long life, and I might change religions three or four times before I die. I’m on the Islam tip—but I’m on the Christian tip, too. I’m on the Buddhist tip as well.”

Beyond their association with the Nation, none of these figures have become the celebrated representatives of modern day Muslims that Ali and X are. Membership of the Nation of Islam does not necessarily conclude with lifelong devotion to Islam, and whilst its reach over the years has been extensive and global, the movement does not typically get recognised as a successful dawah campaign. As the beliefs of the Nation and of Islam have had varying degrees of overlap over time, it is contrived to suggest that the Nation is primarily a platform for dawah at all. Where belief in and practice of religion exists as a vehicle for or even in congruence with social and political agendas, it is a gamble to bet that people will take religion as their ultimate priority.

Present dawah efforts circulate around trying to prove Islam’s worldly functions. Whilst including standard elements of countering enlightenment arguments for utilitarianism, modern Islamic evangelical efforts typically lead with the conclusion of being that which will make everyone happy in some capacity eventually, one way or another. This continues a long-standing shift in the field from traditionally proving Islam using philosophical approaches to contemporarily being oriented around the material purposes of Islam. Though this shift accelerated in the 20th Century, it has been especially pronounced with the advent of Islam deliberately being refined for subculture: an expression of Islam especially curated for mass appeal to people within the current time and a certain place. Enhancing this process is the social media presence of both scholars and laymen illustrating to anyone they can, in whatever way they can, how Islam can cater to their needs.

Islam is able to accommodate cultural differences with the concept of ‘urf, local custom, having a place in Islamic law. However, this exists within limits that are typically neglected or minimised in the propagation of Islam refined for subculture. At the most extreme extent, this results in beliefs totally other to Islam—as with the twelfth belief of the Nation of Islam’s current doctrine. At a toxic and unsustainable extent, Islam becomes weaponised to pursue certain social and political agendas, typically by people relatively illiterate in the nuances of Islamic ruling and well versed in inflammatory rhetoric and social media algorithm. This comes at the cost of a crisis of faith, or marginalisation for anyone that diverges from said agendas (outgroups), but the benefit of exploitative individuals (ingroups).

Currently and very prominently, eager appeals to incel/redpilled men on social media have been made by similarly motivated Muslims (the ingroup), with even a simple retweet of a hadith by a famous incel/redpilled man being sufficient to declare him a compatriot closer to Islam not incel/redpilled Muslims (the outgroup).

Whilst receiving a colder and quieter reception by the Muslim community, the growing White Shariah community follows near identical execution. The method of this subculture closely imitates the method of the last. This entails using Islamic rulings to pursue their favoured agenda and to target members of the outgroup (with different strands ranging their definitions from immigrant Muslims, to Muslims internationally, to ethnic minorities generally, to women) as necessarily degenerate and enemies of the ingroup (white Muslims).

The purpose of this article is not to interrogate the legitimacy of each example of Islam refined for pop culture, or each subculture. Rather, it is to question this overall approach to dawah. Namely, this includes: locating every hot topic; siding with the most appealing group in one’s subjective first person perspective; curating the Islamic content they are presented with and how it is presented with the purpose of increasing the popularity of Islam and legitimising their worldview; fantasising a theoretical utopia; and finally organising a collective group to make that fantasy a reality. If the aim of dawah is to convince people Islam is true in its entirety and keep them convinced of that regardless of social and political contexts, there is little evidence to suggest this approach is the most effective. The viability of this approach becomes even harder to visualise once opposing sub cultures are expected to exist within the same ummah (i.e. the Nation of Islam alongside the White Sharia community).

The Nation of Islam presenting a case study with decades of evidence to learn from, it is legitimate to say that depending so heavily on people’s feelings towards contemporary issues to convey Islam to them limits the extent to which Islam can hold the same weight. Whilst Ali and X became recognisably devoted Muslims, it can not be forgotten that they left the Nation and actively pursued Islam beyond it. People who experienced Islam filtered through the movement, and through chance encounters that followed have not necessarily had the same type of identification with Islam. If the motive for an individual associating with Islam at all is predicated on any contemporary external conditions, and a transient perception of them, this should not be surprising. It should be just as unsurprising if incel/redpill or White Sharia communities reap the same results.

Through the religious lens, the following question is worth asking: Is it better to live and die having never known Islam; to live and die with something falsely related to Islam; or to live and die having Islam running through your fingers, with whatever remaining in your grasp being rationed by the sliding scales of the moment?

Written by Ayah Khanzada